Every day, Madeline Wyatt, GS ’24, moves through a part of Columbia that most students do not know exists. While her peers attend class in Lewisohn and Havemeyer Halls, Wyatt guides her wheelchair through a tunnel system just feet below.

Through cramped corridors, she passes signs that read “DANGER: HARD HAT REQUIRED” and ducks her head to avoid exposed pipes. This, according to Wyatt, is the best option for wheelchair users navigating Columbia’s upper campus.

“The tunnels are better because they’re more reliable, even though you’ll come across many a cockroach and many a Columbia Facilities staff smoking in the tunnels,” Wyatt, a dual degree student in the Sciences Po program, said in an interview with Spectator. “Even with burning hot pipes next to you, it’s just safer and easier.”

Wyatt and other wheelchair users at Columbia contend with a convoluted system of disability infrastructure on the Morningside Heights campus that routinely fails to address their needs. From malfunctioning lifts to sweltering tunnels, the infrastructure meant to improve campus accessibility often inhibits it.

Coupled with the spring 2024 semester’s campus lockdown and ongoing gate restrictions, accessibility for wheelchair users remains a daily struggle.

‘A modern and accessible campus’

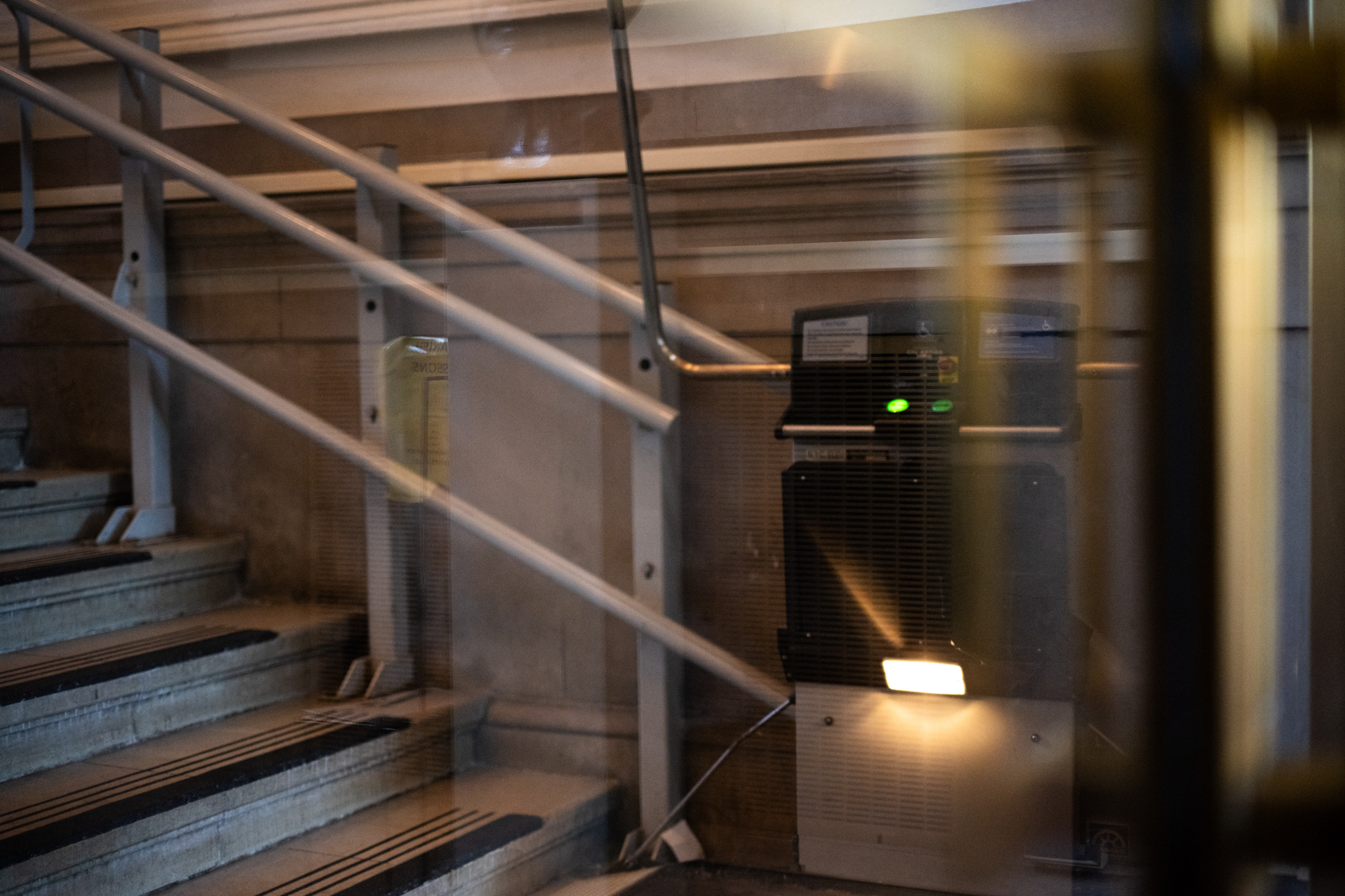

The stairclimber lift at the entrance of Lewisohn Hall. Photo by Isabel Iino / Staff Photographer

The Morningside campus, with many of its buildings constructed in the late 1800s, was not originally designed for the needs of wheelchair users.

Until 2017 and 2019 respectively, accessible options to enter Butler Library and Low Plaza were limited to temporary metal ramps. In a 2022 video released by the University titled “Ramping Up Wheelchair Access on Columbia University’s Campus,” David Greenberg, executive vice president for University Facilities and Operations, highlighted the construction of granite ramps outside Butler and Low Plaza that matched the character of the architecture.

“Our job is not done,” he said in the video. “We’re going to continue to make Columbia a modern and accessible campus.”

Despite these recent attempts at improvement, multiple wheelchair users in separate interviews described the granite ramp that connects College Walk to Low Plaza on the east side of campus as the “ramp to nowhere.”

“It does not connect to the upper part of campus. The only way to the upper part of campus from the lower campus is via an elevator,” Wyatt said. “It is the most useless ramp I have ever come across.”

Other ramps provide access to crucial campus buildings but are difficult for wheelchair users to use.

Jorge Beltran, SIPA ’24, who spoke to Spectator before he graduated, said that the ramp connecting the fourth floor of the International Affairs Building to the street level of Amsterdam Avenue is “too steep” to navigate safely.

Beltran recommended placing mirrors at ramp corners to improve accessibility.

“These kind of things allow us to cohabitate, and it’s not that hard,” Beltran said.

In a statement to Spectator, a University spokesperson described Columbia as being “committed to providing an accessible and welcoming environment” on campus.

“Facilities and Operations has undertaken a number of projects over the past decade to improve accessibility on campus,” the spokesperson wrote. “While great progress has been made, our goal remains to improve disability access over time.”

Leah Ten Eyck, GS ’24, who uses a power chair and spoke to Spectator before she graduated, described the ramps as personally accessible but expressed concern with the stair climbers—a type of wheelchair lift that serves as the main accessible entrance in Lewisohn and Earl Halls, among several other buildings.

“I’m wider than a manual chair, so I do have a problem with many of the older stair lifts on campus,” Ten Eyck said. “The only way I’m able to get on them is that I have use of my legs, so I can flip up my footrest and lose those extra four or five or six inches there. That is something most power chair users cannot do.”

Wyatt described the Lewisohn stair climber as “actively hostile to wheelchair users,” sharing her experience of being stuck on the stair climber for more than an hour due to a malfunction.

“The issue of the stair climber in Lewisohn is that it’s like a one-way street typically. I’ve used it maybe five times now, and of those times, I’ve only had it go back down once,” Wyatt said.

‘Brutal’

Heating pipes line sections of the tunnels beneath Havemeyer and Lewisohn Halls. Photo by Isabel Iino / Staff Photographer

With aboveground accessibility infrastructure prone to malfunctions, some wheelchair users consider traveling through the tunnels to be a more reliable option.

The tunnel system underneath the Morningside campus has a storied history, having allegedly stored radioactive material during the Manhattan Project and facilitated the New York Police Department’s entrance during the 1968 protests on campus. While many tunnels are no longer open to all affiliates, wheelchair users can still use connecting tunnels on upper campus to access Havermeyer, Mathematics, Lewisohn, and Dodge Halls.

Ten Eyck said she is “grateful” to have access to the tunnels.

“I think it’s fantastic that I don’t have to fight for 15 minutes with the stair climber lift every time I want to use that building, but I do find myself actively avoiding those buildings to the point where I don’t really go into GS lounge,” Ten Eyck said.

The tunnels, however, pose their own set of challenges. In order to access the tunnels, wheelchair users must swipe their Columbia IDs, which are registered for disability accommodations. Both Wyatt and Ten Eyck described instances of having doors automatically locking or electronic readers rejecting their CUIDs, forcing them to remain in the tunnels for extended periods of time. Multiple wheelchair users also reported extreme heat in the tunnels, possibly due to the presence of heating pipes along the walls and ceiling.

“You’re a little bit dizzy down there, you know, you’re in this dark tunnel by yourself,” Ten Eyck said.

Another wheelchair user, who spoke on the condition of anonymity citing fear of retaliation from the University, said that using the tunnels in the summer is “brutal.”

The same wheelchair user also described a lack of cell service or internet signal within sections of the tunnel network, making it difficult to contact Facilities for assistance.

“If you’re stuck in the middle of the tunnel, you just have to hope for somebody to come and find you,” the wheelchair user said.

‘An uphill battle’

Signs posted in the tunnels beneath Havemeyer and Lewisohn advise caution while navigating. Photo by Isabel Iino / Staff Photographer

Managing physical accommodations for wheelchair users falls under the purview of Columbia Disability Services, a department of Columbia Health. After registering students for accommodations, Disability Services assigns coordinators who hold meetings to familiarize students with their accommodations.

The wheelchair users who spoke to Spectator largely praised the efforts of their coordinators but expressed doubts regarding the power of Disability Services to improve accessibility on campus.

“I do believe that they’re very concerned about these problems, but I don’t necessarily think that students are able to contact [Disability Services] and then be done with the situation,” Ten Eyck said.

Wyatt described Disability Services as aware of issues with campus accessibility but being limited by “institutional barriers.”

“They’re fighting an uphill battle that the University has very little incentive and very little interest in changing,” Wyatt said.

In a statement to Spectator, a University spokesperson wrote that students who are registered with Disability Services are provided academic and housing resources, as well as event accommodations.

“Students with disabilities, chronic conditions, and temporary injuries are encouraged to register with DS in order to meet their accessibility needs and receive additional support during their time at the University,” the spokesperson wrote.

Despite his experience with the “exhaustive process” of registering for accommodations, Beltran said he has received a lot of support from Disability Services, including additional accommodations for inclement weather.

“I would say generally the staff for University are willing to help all the time,” Beltran said.

While Ten Eyck described Columbia as having “a lot of really awesome services that they offer for disabled students,” she said that Columbia doesn’t properly inform students about these services.

While Disability Services has an onboarding process for new students and provides maps of accessible routes on campus, these resources are not comprehensive. The latest version of the Morningside campus accessibility map available on the Disability Services website does not note the tunnel system as an available route.

Without clear information from the University, Ten Eyck said, students often rely on secondhand information from fellow wheelchair users and support from campus advocacy groups such as the Columbia Student Disability Network.

“I’ve given a lot of tours to students who didn’t know there was alternate entrances,” Ten Eyck said. “I found students trying to drag themselves up stairs because they thought that was the only option.”

Many wheelchair users at Columbia devote a significant amount of time to simply navigating campus. Multiple wheelchair users described experiences with being stuck on various pieces of infrastructure, causing them to miss classes and club meetings.

“It takes time out of my life, and it makes me be late,” Beltran said. “I should be able to be on time, right?”

Ten Eyck estimated that she had missed at least five classes as a result of broken stair climbers.

As a result of increased security measures limiting access to the tunnel system during the inauguration of former University President Minouche Shafik on Oct. 4, 2023, Wyatt had to use the Lewisohn stair climber which subsequently malfunctioned, leaving her stuck. As she waited for 45 minutes for the elevator operators to arrive, multiple people offered to carry her down the stairs. Wyatt said that she appreciated their attempts to help her but found the situation “humiliating.”

“When my autonomy is interrupted by the institutional failings of my University, I’ve lost dignity,” Wyatt said.

‘Columbia with two feet’

Several sections of the tunnels are adjoined to other areas of the building through stairs Photo by Isabel Iino / Staff Photographer

When Columbia restricted campus access in the spring, the University closed its main gates connecting College Walk to Amsterdam and Broadway. As a result, many wheelchair users had to find alternate routes to their classes. Other entrances, such as the gates by Earl and Carman Halls, have stairs and are not wheelchair accessible.

While Ten Eyck described instances in which Public Safety recognized her and assisted her with finding alternatives, she expressed concern for individuals who were less familiar with Public Safety staff or not visibly disabled. She noted that the longer travel times to reach accessible entrances could be detrimental to the health of wheelchair users and other disabled students.

“Students are forced to go down to [the Northwest Corner building], whether it’s because the only elevator here breaks and no one tells us or because they close everything down,” Ten Eyck said, referencing the spring 2024 gate closures.

While these facets of Columbia’s campus, such as the closing of accessible entrances or the conditions of the tunnel system, may not be salient for able-bodied affiliates, they have a significant impact on the daily lives of wheelchair users.

Wyatt described her initial impression of Columbia’s campus as “much more accessible than it actually was.” When she began using a wheelchair in November 2022, she found a significantly altered undergraduate experience from what she had before.

“I really liked Columbia with two feet. You feel really self-important walking up the steps of Low Library, like, ‘I have made it, I worked my ass off to get here.’” Wyatt said. “You feel like you’re really part of something. You feel like you’re welcomed here. But my only way into buildings is through back entrances and tunnels.”

Deputy News Editor Daksha Pillai can be contacted at daksha.pillai@columbiaspectator.com. Follow Spectator on X @ColumbiaSpec.

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter and like Spectator on Facebook.